The Forgotten Federally Employed Artists

Why are the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) artist programs less well known than the Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects for being an instance when the federal government employed artists en masse?

Since the onset of COVID-19, the media have been awash with articles, radio and TV segments, and online discussions about how the hard-hit arts sector might survive the post-pandemic economic crisis. Almost all of these conversations have cited Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration and its employment of artists during the 1930s with the implication — and sometimes outright declaration — that it was the one and only time the federal government employed artists en masse. This notion couldn’t be further from the truth. From 1974 to 1982, federal funds provided employment to 10,000 artists nationwide under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA). We can attest to this bit of history first-hand; both writers of this piece were employed under this remarkable program.

Signed into law by Richard Nixon in 1973 during a recession, CETA was not designed with artists in mind. Originally conceived as a means of training unskilled workers, it was subsequently amended to allow the hiring of trained professionals in high unemployment fields. John Kreidler, an intern at the San Francisco Arts Commission, was the first to recognize how CETA monies could be directed towards artists, and he began using the funding for SFAC’s Neighborhood Arts Project. Soon, similar programs were developed in cities and towns across the country. Accomplished but unemployed artists were hired into positions, many of them full-time with benefits, some of them for as long as two years.

Why are the CETA artist programs less well known than the WPA projects? For one thing, they took place under less dramatic circumstances — an economic crisis not nearly as severe as the Great Depression. For another, they were decentralized: planned and carried out at the state and municipal level rather than under federal administration. For yet another, they were designed primarily for artists to provide public service (such as teaching, project leadership, or administration) rather than to produce individual artworks. While the structure of these programs made them less visible — both then and now — it could make CETA a relevant model for moving forward post-pandemic.

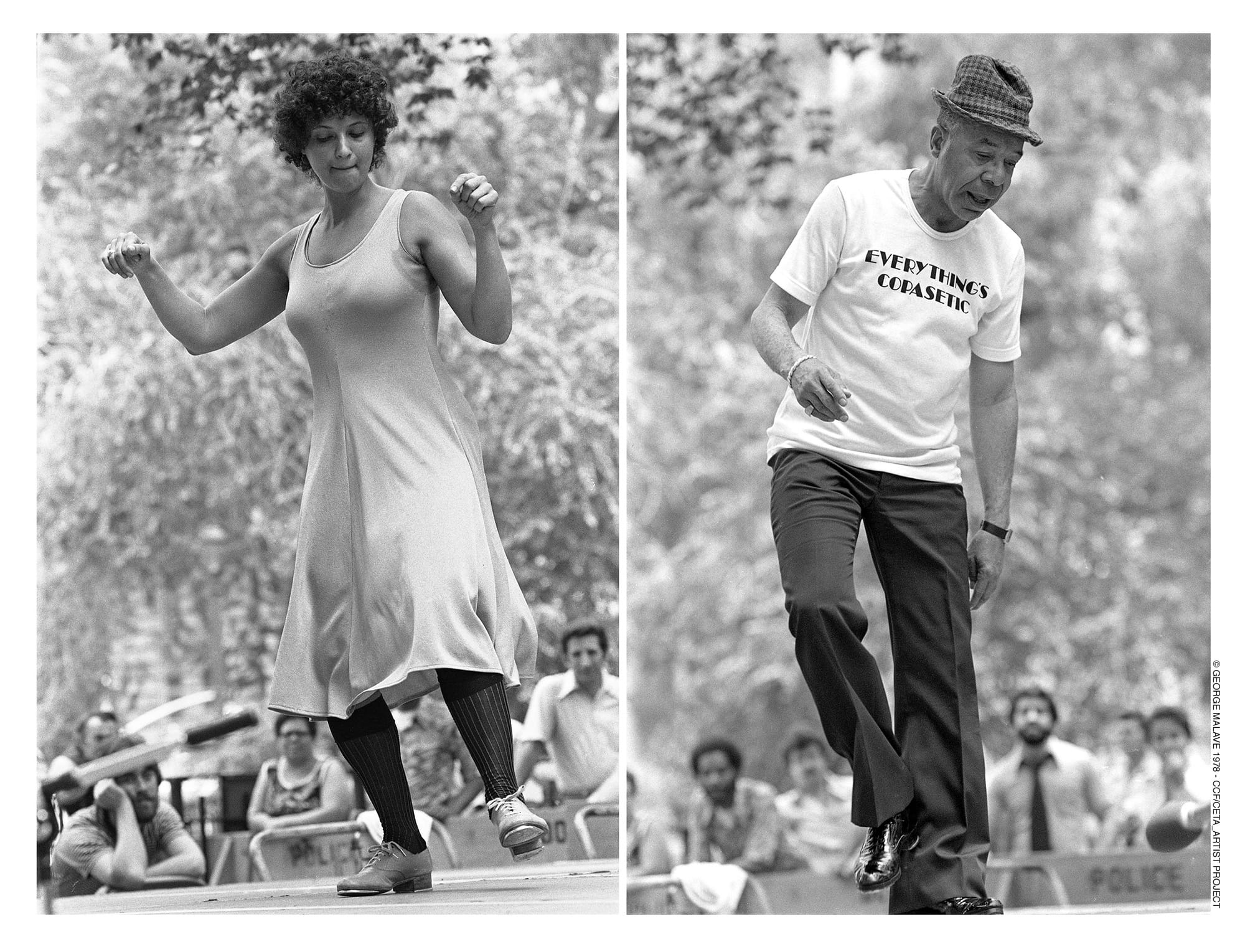

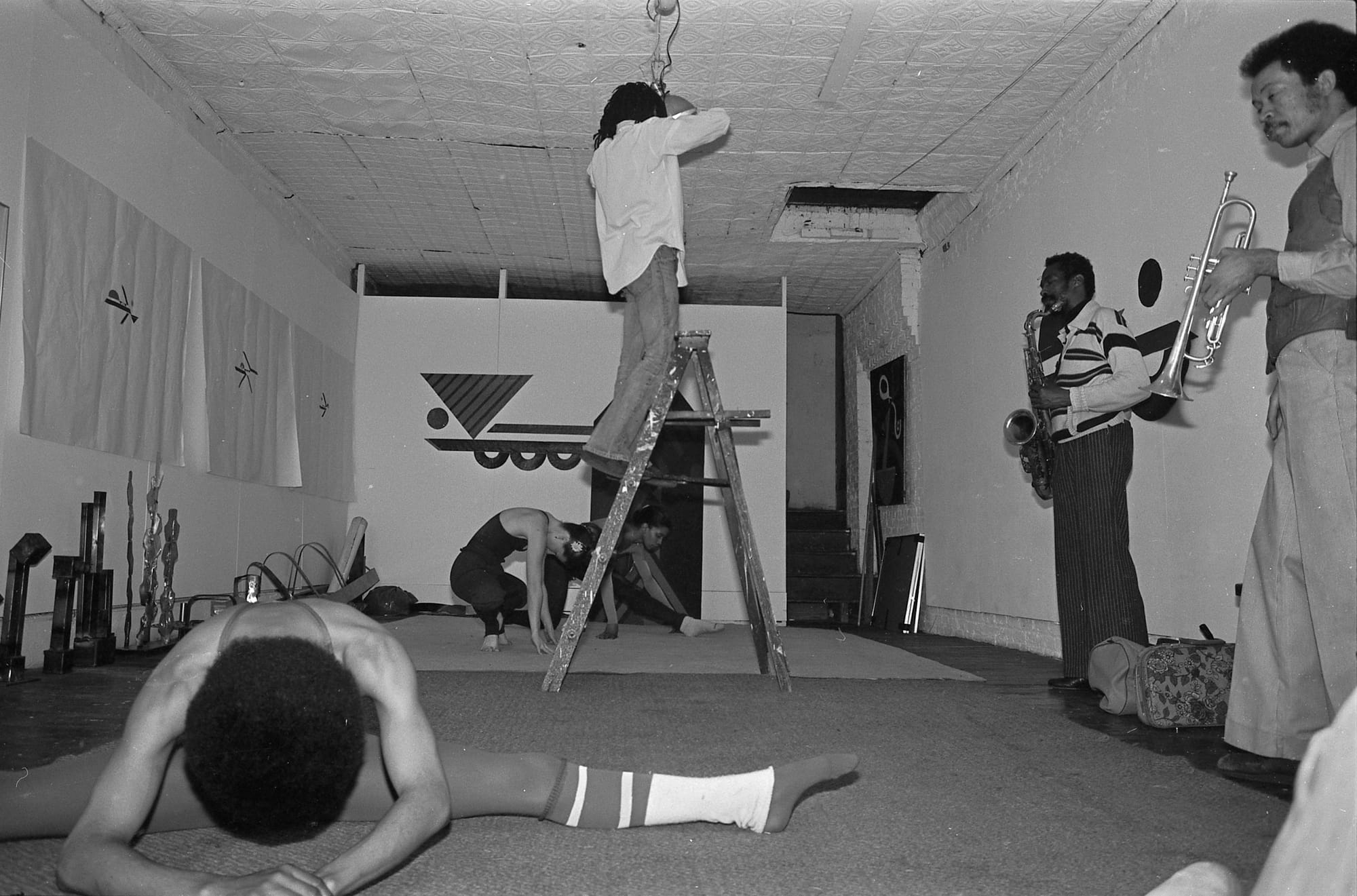

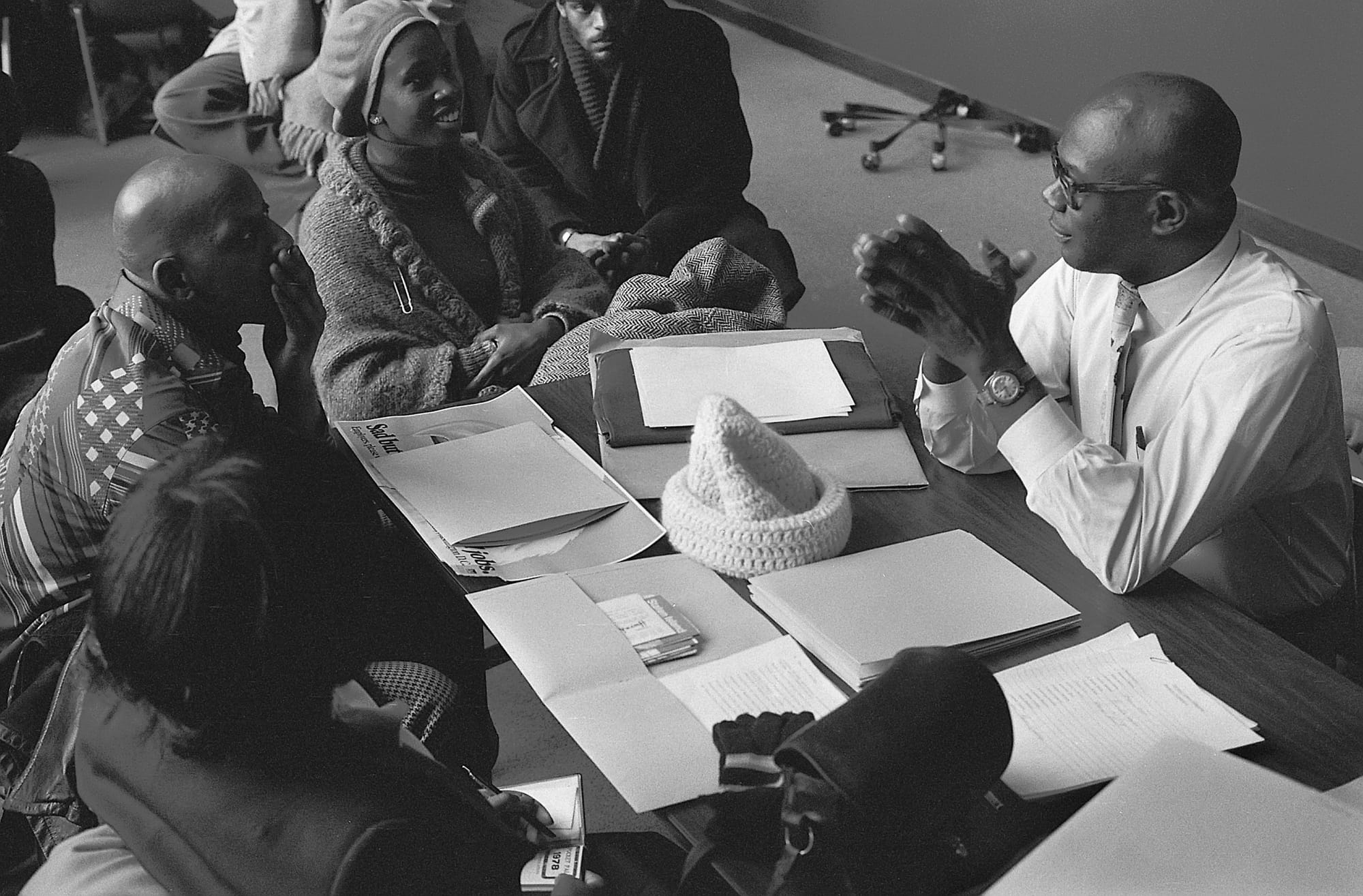

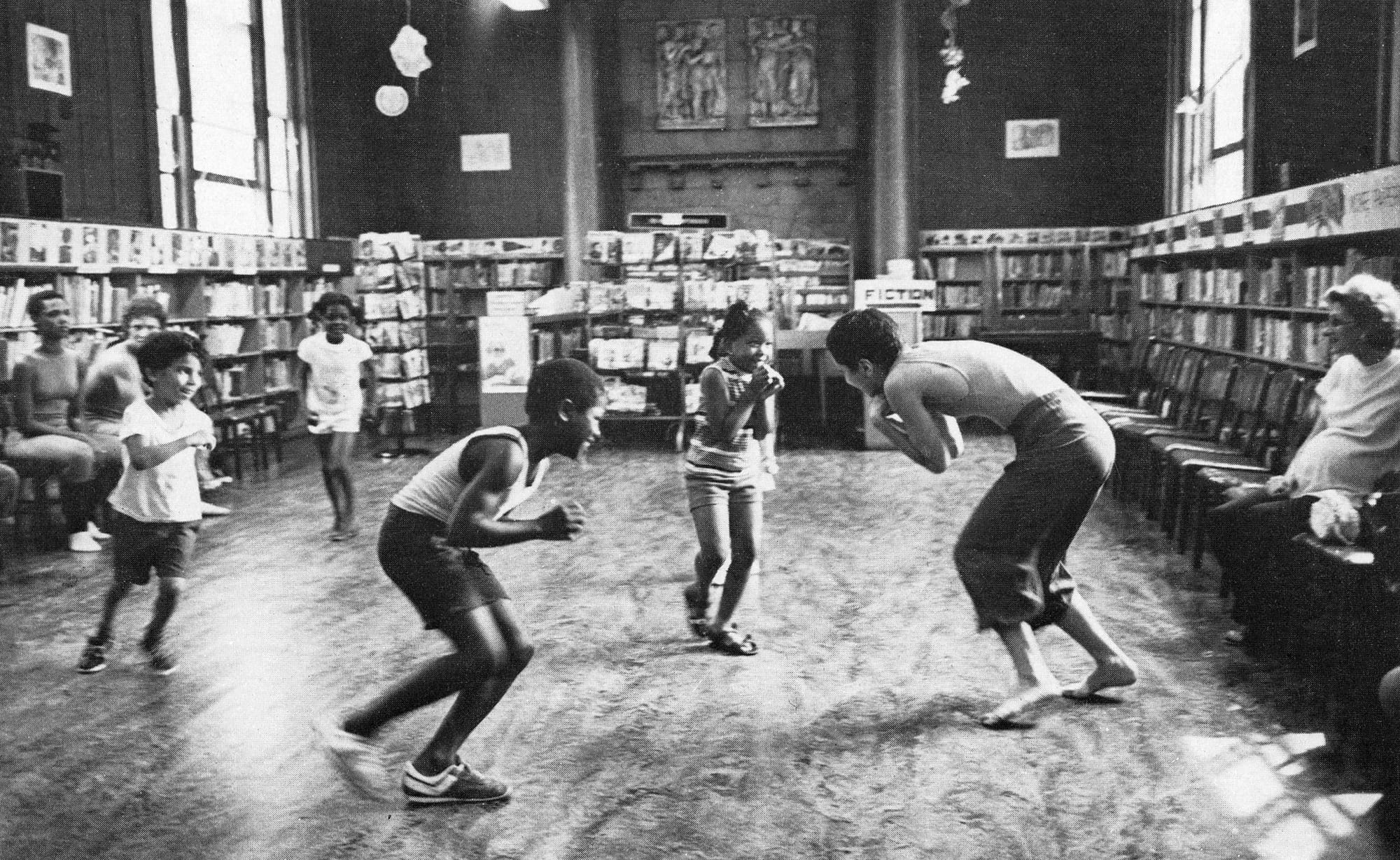

We worked under the largest CETA-funded arts project in the country, the Cultural Council Foundation (CCF) Artists Project in NYC. It and four associated projects employed 500 visual, performing and literary artists. For two years (1978-79) we had full-time employment, each earning $10,000 per year (roughly $45,000 in 2020 dollars), with good health insurance and paid vacation. We worked four days per week in community assignments and one day per week in our studios. Some of the visual artists created community-requested public art works but, unlike the Federal Art Project, this was not a major part of the program. The CCF musicians performed in a number of ensembles, such as the Orchestra of New York and the Jazzmobile CETA Big Band, giving free concerts throughout the city. The media artists worked as a documentary video production unit. Many of the writers became part of a mobile teaching/performing unit called Words to Go. Theater and dance artists, thanks to their full-time salaries, became anchors for their companies.

We were among the project’s youngest artists. (Two of its painters, Joseph Delaney and Herman Cherry, had worked for the WPA forty years earlier!) Our experience proved invaluable to us, not just because it provided a regular paycheck. Through working in different community settings in all five boroughs, we learned how to interact as artists with a wide range of institutional bureaucracies, ethnic groups, and economic classes. We visited areas of the city in which we had never before set foot. In addition, we became part of a network of visual artists, poets, writers, dancers, actors, and musicians that continues to provide us with inspiration and support.

When it came to assignments, CCF acted as matchmaker. Community organizations, schools, museums, theaters, and other nonprofits submitted proposals for CETA artists. While the federal government provided the funds and CCF wrote the checks, it was the sponsor’s responsibility to provide the space, materials, and assistance that their proposal required.

Our assignments took different forms. During the first year, Blaise was a photographer for the project’s documentation unit along with two other photographers, three writers, and an archivist. He traveled to artists’ studios, to performances and exhibitions, to workshops and classes, and to official and unofficial events related to the project. His photos were used in CCF publications and shown in exhibitions. He had an amazing opportunity to learn about the broadly diverse artists who made up the project and their neighborhoods, their sponsors, and the politics of New York City.

In his second year, with the closing of the documentation unit, he was transferred to the general photographers’ pool and worked in three community projects. One was for the Richmond Hill Historical Society, which uses his photographs on its website to this day.

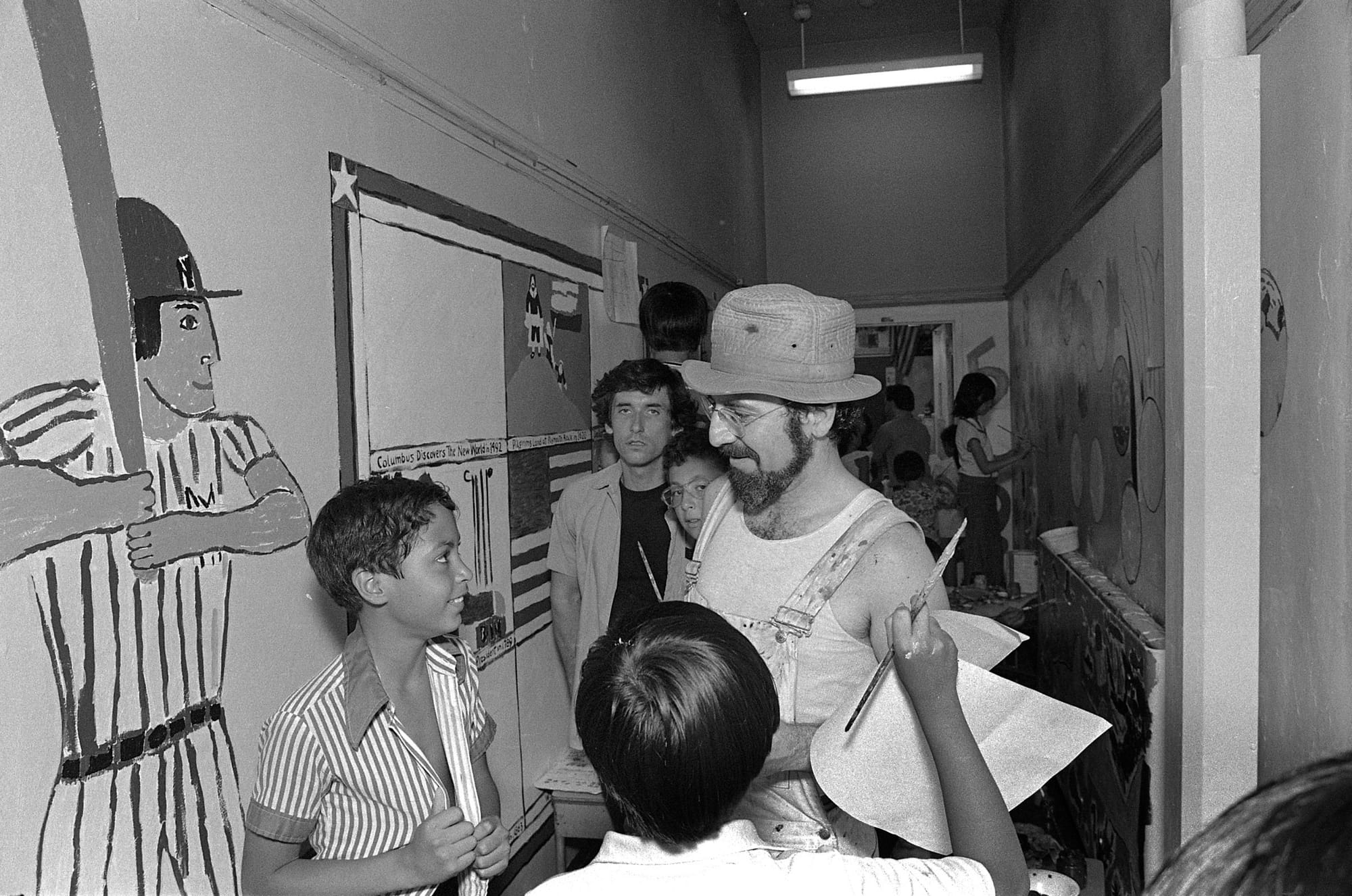

Virginia experienced a variety of placements ranging from teaching children, to renovating an old school, to assisting in museums to creating public artworks. Her work for an after-school program in the Bronx resulted in a collaboration with Charles Biasiny-Rivera at En Foco. They jointly mounted an exhibition of drawings made by the children and photographs made by professionals. While on assignment at the New York Botanical Garden, Virginia helped curate an exhibition of its ethnobotany collection. She went on to create a hand-drawn portfolio of an historic microscope collection, as well as an interactive, concrete sculpture for the Children’s Garden in the Enid Haupt Conservatory.

She was also part of a crew of 10 artists assigned to the Brooklyn Arts and Cultural Association (which became known as the Brooklyn Arts Council in 1987). Under the direction of its founder, Charlene Victor, they converted the former St. Boniface’s School on Willoughby Street into a performance and art space. Their efforts resulted in what came to be known as BACA Downtown, a venue that gave Spike Lee, Danny DeVito, and Suzan-Lori Parks their starts.

Across the country, CETA artists had similar experiences. There were large projects in San Francisco, Chicago, Phoenix, and Washington DC. In other places, CETA funds were used to hire individual artists for service in museums and other nonprofits. No program was perfect, but everyone received a paycheck and many good things were accomplished.

Like the WPA, the CCF Artists Project helped lay a foundation for the future careers of individual artists. It connected artists to communities and to each other. Many of us were able to transition out of the gig economy into sustainable positions. Some found continued employment with their project sponsors while others moved into arts related jobs. Some became professors, museum administrators, arts writers and therapists. Still others went on to artworld success. Sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard and photographer Dawoud Bey were part of the CCF Project. Actors Peter Coyote and Bill Irwin were CETA artists under the San Francisco Art Commission. Judy Baca began SPARC’s Great Wall of Los Angeles with CETA funding and Suzanne Lacy was a CETA artist in a housing project for the elderly in Watts.

CETA particularly benefited African-American, Latinx, Asian, and women artists, not only as individuals but in terms of kickstarting and stabilizing organizations, some of which remain active today. Examples of these still operating institutions include the Black Theater Alliance and the Association of Hispanic Arts in NYC, the Brandywine Workshop in Philadelphia, and the Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul.

As well, museums and cultural institutions across the country benefited from the CETA funding of support staff. In NYC alone, there were 300 CETA employees in maintenance, security, and other positions. The Philadelphia Museum of Art had at least 38 CETA staff lines, particularly noteworthy given that the pandemic has forced the museum to lay off 85 employees and “voluntarily separate” 42 more.

CETA’s employment of artists was money well spent. The investment was returned to society manyfold in the form of taxes paid, services rendered, real estate values increased, neighborhoods revived, and an overall economy made more vibrant. NYC’s cultural plan, CreateNYC, highlights CETA as a model for economic support of the arts.

What would it take to allow a jobs program like CETA to happen again? The will to do so, along with the right approach.

Joe Biden has long been an advocate for government funding of the arts. According to Kate Shindle, president of Actors’ Equity who was recently quoted in The New York Times, Biden recognizes the arts as “a critical driver of healthy and strong local economies in cities and towns across the country.” This view underscores a CETA-like approach.

The Biden administration will have to address massive un- and under-employment across all sectors of society. A broadly defined jobs program that includes the arts would be a much more fruitful avenue for recovery (and more acceptable to the public) than relief in the form of grants for creative activity. Employment programs could actually direct more total support towards artists. This was the case with CETA, which, at its peak in 1980, funneled more than $200 million—$900 million in 2020 dollars—into arts employment while the total NEA budget that year was only $159 million.

Given Republican advocacy for diverting decision-making away from the federal government and for returning power to states, an updated version of Nixon’s “new federalism” might help CETA-like legislation through Congress. Another benefit of the CETA approach is that it relied upon partnerships between government entities and private nonprofits. Such partnerships, intended to increase efficiency within the public sector, often enjoy bipartisan support. Clay Lord, Vice President of Strategic Impact at Americans for the Arts, has crafted a comprehensive arts employment proposal designed to help the new administration hit the ground running.

What happened 40 years ago can happen again.